Back to the Start

Story’s End

This game begins at the end of a story; whilst the game moves forwards in time, the story is revealedbackwards, starting at the end and working towards the beginning. Within these rules, where the ‘game’ is referred to, then cause is followed by effect; where the ‘story’ is mentioned though, effect is followed by cause.

The game begins with the end credits of the story, which tells us about the characters we have just watched. The credits will be represented by a pile of cards in front of the players, which will list all the traits and conditions that were possessed by the characters in the story. To start the game, the players take 2 or 3 blank cards each, depending on the length of the story; on one side of each card, they write a trait for a character. Character traits should be attitudes, histories and talents:

- Attitude: short-tempered, ambitious, over-confident, stressed, cynical.

- History: war veteran, ex-con, disgraced, fired, engaged, recovering alcoholic.

- Talent: stunt driver, sharp shooter, tough, beautiful, clever, rich.

Once the traits are written out, gather up the cards, turn them over and shuffle them, then deal them out again; on the blank sides of the cards, the players this time write down a condition. Each condition is a measure of the state that the character ends the story in, such as:

- Their physical well-being, e.g. dead, dying, injured, sick, crippled, comatose.

- Their social status, e.g. fired, imprisoned, accused, bankrupt, popular.

- Their location, e.g. missing, at home, marooned, in the White House, buried alive.

- Their achievements, e.g. victorious, loser, beat the bad guys, found true love, saved the world, took the blame.

The Final Scene

Prior to the end of the story, there will be a final scene that wraps things up; any player seated around the table can start the game by framing this scene, in the form of a Shot. A Shot is simply a cinematic description of the location of the scene and the general mood. When describing a Shot, you should consider some or all of the following:- Where is it? Describe the location of the Shot: indoors or out, day or night, the past, present or future.

- Who is there? Describe any characters who can be seen in this Shot, but only their appearances and actions, e.g. what we can see. Don’t try to explore their personality or motivations just yet

- How do we see it? Describe the camera work being used on this Shot; are we seeing a normal frame of TV or film drama? Or is it a steadicam shot, a PoV shot, a night vision shot? Or even something stranger, like a telephoto shot from a plane or satellite far above the action or a still frame in the form of an artist’s rendering of the scene?

- What’s happened? Describe any event that ends the scene, such as a car wreck, an explosion, someone walking out, a gun being drawn, a door breaking down. Consider the use of SFX and CGI in describing this.

Keep descriptions short and to the point, don’t

be tempted to ramble on and bear in mind that all narration flows backwards

through the game; the Shot you describe is what happens after the scenes which are still to be narrated.

Example (Part 1): For example, Dave narrates the end of the Final Scene with a Shot depicting the burning ruins of a high school, with a small number of ragged looking teenagers looking on with expressions of grief and grim determination.

Any

other player may then pick up the narration by describing the Shot, Line or

Action that precedes the one just narrated. A preceding Shot is described using

the same guidelines as above; in order to deliver a Line or perform an Action,

you must have a usable character card in front of you. If you have none, take

the top condition off the character pile; at the end of the story, all the

characters have exited the fiction, so the first time any player draws a

character card, they must also narrate how that character leaves the story

based on the condition drawn.

Any

other player may then pick up the narration by describing the Shot, Line or

Action that precedes the one just narrated. A preceding Shot is described using

the same guidelines as above; in order to deliver a Line or perform an Action,

you must have a usable character card in front of you. If you have none, take

the top condition off the character pile; at the end of the story, all the

characters have exited the fiction, so the first time any player draws a

character card, they must also narrate how that character leaves the story

based on the condition drawn.

Example (Part 2): Tony

follows Dave’s narration with a Line or Action that precedes it; to do so

though, he needs a character, so he takes the top card from the character pile,

a condition that says ‘Dead’. This means that his narration must first describe

the death of that character before he can continue with the events prior to

their death.

Lines: A Line is any piece of significant

dialogue delivered by a main character;

minor characters can speak but they never get the important Lines, so

their dialogue can be included as part of any narration. As with everything in

this game, each Line follows the next

narrative event in the game; at the start of the game, when the story is being

wrapped up, Lines may often refer to the events the characters have taken part

in but which have not been portrayed in the game yet. When delivering a Line,

consider some or all of the following:

- Who is saying it? Give some thought to the character and the way they express themselves, as well as what their role might turn out to be as the game is played.

- Who are they talking to? Is there another character they are addressing or a group of them? Or are they just making their statement to the world in general?

- How are they speaking? Are they loud, quiet, in pain, happy, sad? Are they whispering discreetly, talking on the phone, recording their speech on tape, appearing on live TV?

- What are they saying? Consider the impact of their words carefully and bear in mind that it may be the answer to the Line that follows it in the game.

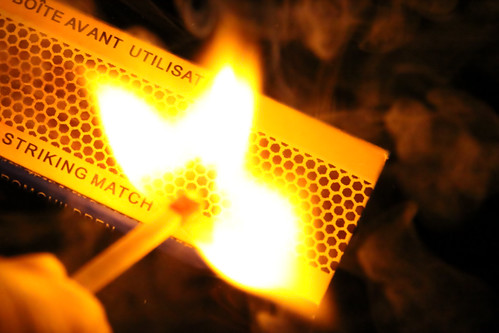

Example (Part 3): Tony

describes how, as the high school burns, one person is trapped in the flames; his last Line, before he meets his fiery demise, is “No! The money!”

Example (Part 3): Tony

describes how, as the high school burns, one person is trapped in the flames; his last Line, before he meets his fiery demise, is “No! The money!”

Actions: An Action is any significant event

that involves the main characters; there are plenty of minor events and minor

characters caught up in them, but these are all encompassed within any

narration. Actions are one of the major tools for changing the course of the

story; after narrating any Action, the players should consider why it happened

and use that to inform later narrations. When performing an Action, consider

some or all of the following:

- Who is doing it? As with a Line, consider the character who is performing the Action.

- How are they doing it? What tools are they using for this action? What condition are things in? Are they being fast & panicky or slow & methodical?

- Who are they targeting? Is this something for themselves or is it intended to affect others?

- What are they doing? It is likely that their Action is a direct result of something that will be narrated later on in the game, so again, use it to set up the events that preceded it.

Example (Part 4): Richard

goes next and grabs a character card that says ‘Survived against the odds’, so

he describes one of the teenagers desperately running out of the school with his

clothes on fire; he rolls on the grass outside to put out the flames.

Play continues in this fashion, with players

taking turns to suggest Shots, Lines and Actions within the current scene;

there does not need to be any particular order to these contributions, but you

are encouraged to police yourselves to ensure that everyone who wants to speak

gets a chance to do so and no-one is allowed to dominate the group or over-ride

anyone else.

Conflict Management

Conflict occurs within the story told as it

does in any story, but from the perspective of the game, there is no conflict,

only convergence. As each narrative event occurs chronologically after the

events that follow it, there is never any question over whether a particular

end is achieved: ends are portrayed before the actions that set them in motion occur

or the motivations for them are known. Unlike other RPGs then, Back to the Start doesn't use a system

of ‘conflict resolution’ and characters don’t compete with each other to

accomplish their goals. The resolution mechanic used in this game is one of

convergence; when events take place, players may disagree about their causes

and the resolution of that disagreement allows one player to provide the

explanation for that event.

If

a point is reached in any scene where two players disagree on the delivery of a

Line or the performance of an Action, then they each put forward a character

they control to take part in a convergence check. Each trait and condition

begins with a score of 1, which is the number of dice rolled when using that

card in a convergence check; every time that character wins a convergence

check, the score for the trait or condition used goes up by 1. The winner of a convergence check is the

character who gets the highest total on their dice; in the event of a tie, both

sides roll all their dice again.

In

order to use a character card, the trait or condition on it must be appropriate

to the point of this scene, either by contributing to the overall plot of the

story or to the character’s own personal story arc. The winner’s narration

should in some way either foreshadow the condition used or strengthen the

trait; in doing so, they may also fix some of the motivation for the

character’s involved, by establishing how or why they have achieved what has

happened. This can be done by mixing Shots,

Lines

or Actions or simply by stating that it is so and leaving it to be portrayed

later in the story.

Example (Part 5): Dave

follows Tony & Richard by also grabbing a character card, which says

‘Victorious’ and he describes a cheerleader lighting the matches that start the

fire... but Richard has in mind that it was his character who started the fire,

so they go to a convergence. Both players only have conditions with a score of

1, so they each roll 1d6; Richard rolls 3 and Dave rolls 5, so he wins and

carries on with his narration, but he also increases the score on his

‘Victorious’ condition from 1 to 2. In his narration, he includes the

triumphant look on the cheerleader’s face as she watches the flames take hold

before running for the exit.

Character Development

Characters change and develop through the

course of the story, but naturally this character development is seen in

reverse order during the game. Major developments occur during convergence

checks; if you imagine running the story in its correct order, a convergence

becomes a turning point, when the actions of the characters take their own personal

stories in new directions. The type of

development depends on whether a condition or trait was used in the

convergence:

Conditions: Whenever you get a pair of

identical results on your dice when using a condition in a convergence check,

flip that card over to its trait side. This is the crucial turning point for

that character in the story, when they move from being the person they were to

setting out on the course of action that will decide how they arrived at that

condition later on in the story.

Traits: Whenever you get three identical results on your dice when using a trait in a convergence check, discard that character card; this is the moment of the story when that aspect of the character’s life is first explicitly dealt with by them. If it is the last card possessed by that character, this is also the scene in which that character enters the story and therefore their last scene in the game.

Example (Part 6): On

Tony’s turn, he has his character with the cheerleader in the school gymnasium,

saying “I’ll grab the bag and meet you outside.” Dave questions why the

cheerleader is apparently working with the man who burns to death in the

school; is this a trick or did she betray him? They go to a convergence check;

Tony rolls 6 for his condition and Dave rolls two 2s, for a total of 4; Tony

gets to narrate the ‘why’ that precedes this Line, but included in this is the

turning point for the cheerleader’s character. Flipping the character card

over, Dave reveals that the trait on the other side is ‘Rich’ so he adds that

the bag of money belonged to the cheerleader in the first place.

Counterflow

It’s understandable that players may struggle

to adequately describe what is taking place in the

story; constantly having to think backwards can be a great strain on even the

most creative mind. Provided here are some tips and general guidance to help

you through the process.

Exits & Entrances: The first time in

the game that you draw a card from the character pile, you are narrating the

way in which that character exits the story, based on the condition on that

card. If you already have a character card in front of you, then when you draw

a new card, you choose whether to create a new character and describe their

exit, or attach that condition to an existing character you have created, if

you can do so. Adding conditions to existing characters is often impossible,

unless the game played up to that point fits that condition, e.g. if you've

been playing a character for a few scenes, it’s impossible to add a condition

like ‘Dead’ or ‘Comatose’ to them, since they clearly weren't either of those

in the scenes that have been played.

Later

in the game, when you discard a character’s last card, you must narrate the

point at which they first appear on screen, based on the trait used; the

character may still be referred to in the scenes that follow, but they cannot

appear in them, since they have not entered the story yet.

Hows & Whys: As the narrative of the game

runs backwards, so too does the normal narrative structure, with the results of

events being portrayed before the events themselves. When framing a scene then,

you are often looking for a way to set-up or explain the events that have

already been portrayed in the game, rather than exploring the consequences of

prior events as you would in most other games. You can use this to your

advantage to narrate in any kind of scene you can imagine; for example, if you

want there to be a scene on the Eiffel Tower where you push someone off it, you

can do so without having to build to that point over several scenes, with no

certainty of ever getting there. Grab the scenes you want when you want them

and worry about how they fit into the narrative afterwards.

The

best way to think about the story is to try to answer the questions ‘How’ and

‘Why.’ The first refers to the way in which things happen: if the Eiffel Tower

was portrayed in an earlier scene of the game, you might choose to have a scene

showing how the characters got there, which can be told largely through Shots and Actions. The second provides a reason for things to happen: what caused

the characters to go to the Eiffel Tower? This can be answered well with Lines and Actions. The questions of how and why also drive scenes towards

convergences.

Responsibilities: Once the game gets going,

everyone will not only be responsible for the behaviour of their own character,

but will start to pursue their own plot threads. Each player will have a

slightly different version of the story mapped out in their head, formed of

assumptions and inspirations: it’s good to be invested in the story, as this

will make it more interesting for all players, but don’t become possessive. You

may be participating with some cool storyline unfolding in your head,

anticipating where things will end up, but so is everyone else and their

version of the story will not match yours. Taking ownership of certain strands

of the story is to be encouraged, but you must allow that other players’

strands may tangle with yours and tug them both in unexpected directions. Never

insist that the story unfolds in the way you have planned for it, allow it to

be shaped and guided by the input of all players and let the big decisions be

made by convergences.

No comments:

Post a Comment